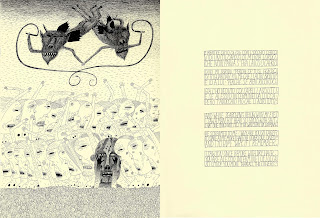

Inferno XVIII: Fecal Matter

Ink on paper, 2016

22 x 15”

Dante has arrived in the eighth

circle of Inferno, in the first of ten pouches (ditches) called the malebolge

(translated as “evil pouches”). Here he witnesses a band of panderers

(pimps, flatterers, et al), tormented by demons as they move in procession along the floor of the valley His gaze is arrested by the sight of one pathetic

sinner whom he recognizes, covered with a thick layer of excrement.

* * *

Dante’s cruel sarcasm is on full

display in his exchange with Alessio Interminei of Lucca, a flatterer who asks

Dante why he feels compelled to stare him down more than the others. The retort

is mean-spirited and antagonistic:

"Why, if I remember,

I saw you once before with

dry hair.

You are Alessio Interminei

of Lucca,

so I study you more than

all the others.”

Dante’s towering literary

reputation sometimes overshadows his arrogance and cruelty. He can be a tool, but he’s still

funny as shit.

This is a shitty drawing in more

ways than one. I’m pleased enough with the bottom half, but the top surrenders

itself to whimsy, my eternal predilection. Not that whimsy can't be terrifying. Just ask the two foolish children who, lured by promises of treacle tarts by the androgynous, superficially mirthful Child Catcher, met sudden, horrifying entrapment in Chitty, Chitty, Bang, Bang. The bottom of my drawing is certainly whimsical,

but there is to me more perversity in the characterizations and the way lines,

visual hierarchy, and other formal/design decisions contribute to a sense of severe agony in its figures. I need to do something about the demons—they’re a bit

more like characters from The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show than the fierce

antagonists they’re meant to be. Maybe I’ll simply obfuscate them in an inky

cloud. Things are scarier when you can’t quite see them.

I need to study how imagery evolves

this way for me, how some parts go wrong while other parts seem to fall in

place almost effortlessly (although I should be careful to say that nothing

ever feels effortless); how sketches sometimes seem more essential and honest

than finished drawings or, conversely, how finished drawings finesse the seeds

of simple ideas into more sophisticated form. I had a wonderful student once,

Matt Leines, who had undertaken an independent study project with me. We met

every week to discuss his ideas, and I recall at one point he came to me with

an expression of frustration. He had a sketch—small and in a notebook—and he

had a finished illustration—a bit larger. His question was simple: “why doesn’t

this look like that?” In other words, what was it about the sketch that he had

been unable to apprehend in the finished image? We went round and round

and—apart from the typical technical explanations (eg.: perhaps his use of

mediums didn’t translate well at larger scale and on a different substrate?) I

think we ultimately decided that sometimes the honest impulse for mark-making,

the exploration of form and meaning in its most naive, open and meandering mode

of drawing and painting, is impossible to replicate.

So, some things turn to shit.