Sunday, November 2, 2014

Monday, September 22, 2014

Wednesday, August 27, 2014

Sunday, August 3, 2014

Saturday, June 28, 2014

Tuesday, June 24, 2014

Sunday, June 22, 2014

Important and Unread.

Running renders more universal the consciousness of very different people—traversing without prejudice occupations and political inclinations, age and gender. That's the most enjoyable social aspect of what is primarily an individual sport: running requires but one player, and yet it unites countless souls in the shared cadence of footsteps and breath, the rhythm of minutes, seconds and hours.

Lately my running companions have included a postal worker, a librarian, a yoga teacher, a humanitarian aid researcher (who also happens to be my partner), a few college professors, a banker, a press agent, a physiatrist and two surgeons. One of the surgeons is the same age as me, transplanting kidneys and other vital organs for a living. When I am with him I think about how distinctly different our perceptions of the world must be. He has not only seen the inside of a living body—heart quivering, innards churning away—he has come to know intimately that secret world, slicing, sponging, suturing. I have not. If ever I have the occasion to cut into a human body, I am sure I will be a changed man. An invisible infrastructure of intertwined channels of swishing blood and densely packed organs and bones is animated beneath the skin, while we go about our business: sleeping, washing dishes, reading a book. This realm of knowledge and experience joins three others which seem inexhaustibly vast to me: the study of physics, the conundrum of educating of our children and the complex structures of philosophical thought.

* * *

I first saw a dead man on Memorial Day. It was a profound experience. I had spent the weekend in Boston with my partner and our three dogs, and was driving home to Rhode Island in the late afternoon on route 93. The dogs were in the back seat, piled on top of one another and sleeping off the weekend play. The traffic wasn't particularly heavy, but—typical of New England highways—there were plenty of us on the road, hundreds of people lamenting the return to work the next day, after a day of cookouts and badminton, woven lawn chairs and mosquitoes.

Cars were all around me, driving 60-80 miles an hour, when a motorcycle came racing up from behind on my left. He hot-dogged it a little, but not too much—weaving in and out poetically, enjoying the lyrical movement of the bike. The motorcycle was bright red, and the man driving it was well-covered in dark, thick clothing, because May can be cold up here. I said aloud, as I always do, "that guy's going to kill himself." He disappeared quickly beyond the cars in front of me.

Two minutes later traffic slowed abruptly, with everyone braking to a crawl. That's when I saw him. He was on his stomach in the middle of the highway, one arm stretched over head, and the other wrapped beneath, crossing his chest. The red bike peppered the asphalt in dozens of pieces. There was no blood. Several cars had pulled over only seconds earlier, and dozens of people were running toward the oncoming traffic. One man was in sandals and tee-shirt, suntanned and chubby. He was running as fast as he could, trying to steer clear of cars. His barrel chest jiggled beneath his horrified face. I had arrived only seconds after the crash, and the poor man was clearly dead, a whole life and world unknown to me had come to an end. I could only continue moving, because to stop would have caused even more pandemonium with three dogs in the back of the car. There were already many, many people on the scene, trying to know what to do. Several were on their phones with panicked expressions on their faces. A woman was crying.

The dead man's helmet was on, completely obscuring his identity. Mercifully spared a glimpse of his face, I nevertheless thought repeatedly about this awful moment over the next several hours, and into the next day. I began to scour the internet, googling succinct phrases: "motorcycle accident, dead, 93, memorial day, crash." Almost immediately I found a very brief report, which described little more than the superficial facts: a man had lost control of his motorcycle on Memorial Day on route 93 near Canton at around 3:30 in the afternoon. He was pronounced dead at Boston Medical Center. It was a red Yamaha. He was 33. I checked every day for a week, and learned no more. The police were withholding his name.

A little time passed and I stopped checking, going about my business. I forgot about him for a while but was reminded one day to continue the search. I found out his name was Maxim. I learned his last name too. He was from Kazakhstan. He must have been well-liked because a fund had been established in his name and thousands of dollars had already been collected. I found pictures of him with his buddies, posing in front of statues, sitting on a horse, sitting on his red motorcycle. Short-cropped hair, with a monkey on a beach. Thumbs up with a snowman in winter, and shirtless with a surfboard. Always smiling. Slightly crooked teeth, solid build. Happy.

I don't know why it felt so important to find him, to put a name and face on the heap of muscle and bone in the middle of the highway. It wasn't morbid curiosity and yet it had less to do with preserving his dignity or as an expression of sympathy than it did with longing to be connected to one another through the human condition. I first saw him in a moment of violent, chaotic death, and that alone wouldn't do. Our shared experience—his and mine—felt incomplete without learning who he was, what kind of life he'd lived and the unknown world he left behind.

Labels:

miscellaneous blather,

musings,

writing

Friday, June 6, 2014

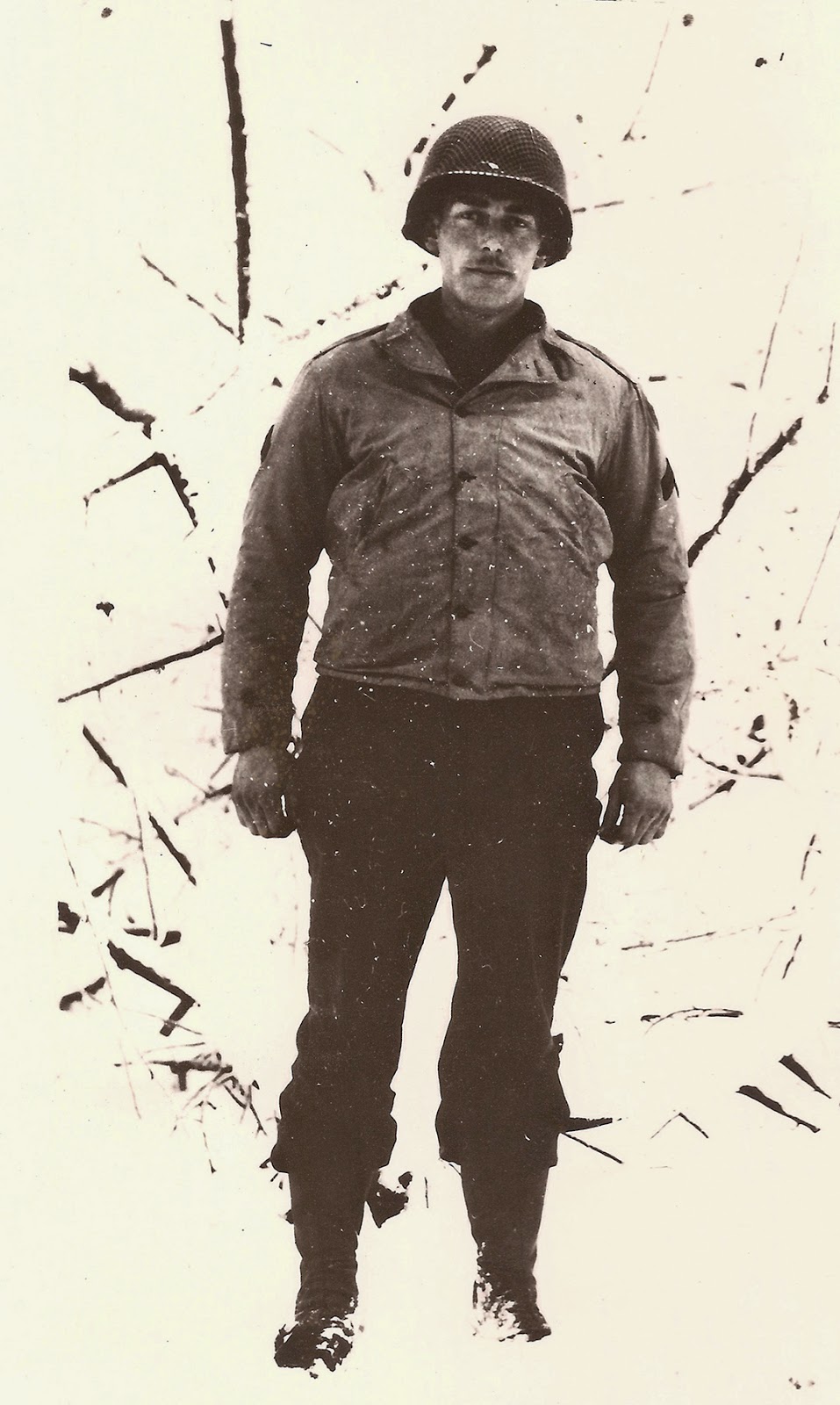

D-Day: A Melancholy, Heroic Life.

In doing some genealogical research last winter I uncovered (online, of all places, and quite randomly) the passport applications of my grandparents, my uncle and my father—eerie snapshots of a young family about to embark on a new life in Europe, not knowing that the man of the house would be dead within months. My father was 3 years old. He's the small child in the center of the third photograph.

Dad learned to swim when he was thrown off a bridge by his bully of a brother (five years his senior, aided by a bunch of neighborhood toughs). With his father dead and his brother a juvenile delinquent who spent most of his time carousing with other punks from the neighborhood, my dad was left to wait on a house full of spinsters and widows. His mother returned from Germany to Atlantic City to be with her sisters and mother for many protracted years of mourning (I have seen photos of her in black dress and veil in bright sunlight on the Boardwalk—a frail, inky specter of grief who couldn't let go of loss). My father lived in the big, old, tudor house at 4710 Theresa Place with his grandmother, mother and four maiden aunts, all psychically exhausting women who knew nothing of responsibility, having been pampered all their lives by their father, a wealthy railroad man who had long since left behind life on earth and a comfortable salary. But there were stories of fun (or, at least, funny) times too. My dad bragged about having broken too many bones to count with stunts like jumping from balconies with his neighbor and boyhood pal Billy Fox. He loved hanging out on the beach all day to idolize the legendary Atlantic City lifeguards, and he told me stories about beating sand sharks to death on the shore, just for the hell of it, of sun poisoning, and of cutting open his palm while trying to skim slate over the ocean waves. One of the brightest moments of his life occurred in October 1927, when Charles Lindbergh landed his plane at Bader Field in Atlantic City, following his earth-shifting, heroic transatlantic flight. My father had laid in the grass all day, his nine-year-old eyes scanning every inch of the sky for the wings of the Spirit of St. Louis, inscribed with large block letters: NX-211. He saw the plane fly right overhead and rushed to the airport. What a thrill that must have been.

My dad had a long and challenging life. He grew up in decadent, mob-infested Atlantic City in the 1920's and 30s. He told the story from time-to-time of watching from his window as Dutch Shultz' men shot from the bushes of the house next door at windows on the second floor. When I was about ten, I found a photo of him at the same age. If not for the uber-masculine, defiant expression on his face, I was looking in a mirror. There he was on an Atlantic City sidewalk, dressed in a shirt and tie and sitting on a pony: chin thrust forward, scowling brow, piercing blue eyes. I remember having the uneasy feeling that he would have been my nemesis if we had been boyhood neighbors. He scared me.

Dad learned to swim when he was thrown off a bridge by his bully of a brother (five years his senior, aided by a bunch of neighborhood toughs). With his father dead and his brother a juvenile delinquent who spent most of his time carousing with other punks from the neighborhood, my dad was left to wait on a house full of spinsters and widows. His mother returned from Germany to Atlantic City to be with her sisters and mother for many protracted years of mourning (I have seen photos of her in black dress and veil in bright sunlight on the Boardwalk—a frail, inky specter of grief who couldn't let go of loss). My father lived in the big, old, tudor house at 4710 Theresa Place with his grandmother, mother and four maiden aunts, all psychically exhausting women who knew nothing of responsibility, having been pampered all their lives by their father, a wealthy railroad man who had long since left behind life on earth and a comfortable salary. But there were stories of fun (or, at least, funny) times too. My dad bragged about having broken too many bones to count with stunts like jumping from balconies with his neighbor and boyhood pal Billy Fox. He loved hanging out on the beach all day to idolize the legendary Atlantic City lifeguards, and he told me stories about beating sand sharks to death on the shore, just for the hell of it, of sun poisoning, and of cutting open his palm while trying to skim slate over the ocean waves. One of the brightest moments of his life occurred in October 1927, when Charles Lindbergh landed his plane at Bader Field in Atlantic City, following his earth-shifting, heroic transatlantic flight. My father had laid in the grass all day, his nine-year-old eyes scanning every inch of the sky for the wings of the Spirit of St. Louis, inscribed with large block letters: NX-211. He saw the plane fly right overhead and rushed to the airport. What a thrill that must have been.

Having left for the University of Virginia, where he was president of his fraternity and captain of the swim team (but unhappy in both roles because, as he said, his main responsibility was to keep drunk college boys out of trouble), my father enlisted post-college on 13 December 1941 and was shipped off to Europe to join the allied forces. Twenty-three years old, he indicated on his enlistment form (which I also, miraculously, found online) that his occupation was "actor." This puzzled and amused me; my mom explained that he and Billy Fox, unsure of what their lots in life would be, had planned to leave for Hollywood and make it in show business. "We're both good-looking fellas" Billy had said.

My dad was (tragically) on board the Queen Mary on 27 September 1942, when it cut through the much smaller British cruiser, HMS Curaçao, killing 329 of the 430 men on board. On his way to join the allied forces of the War, he was sleeping in his bunk after a night of duty (in what was once the cocktail lounge of the luxury liner during its non-military years) when the Queen Mary rammed the Curaçao. I have some articles about that too—one with a photocopy of the Queen Mary marked up with his meticulous handwriting, noting the position of his quarters on the ship.

My mom became a voice for whatever war narratives he would allow to unravel. The most harrowing of these experiences may have been his involvement in the battle of Normandy on Omaha Beach on D-Day, exactly 70 years ago today. Undoubtedly, he experienced both grief and intense fear, and while news media contacted him many times over the years to tell his story, he always declined. I've learned over the years that many of those men were reluctant to discuss the experience. It must have been horrible. I feel fortunate that he did relate the facts to my mom, who is now 94. She shared this brief account of his experience in 1998:

Hank Brinkerhoff was with the famed 29th Division. The 111th Field Artillery (his outfit) followed the 116th Infantry Regiment, the first to arrive on Omaha Beach on D-Day. The 11th were to be the infantry simultaneous back-up but the DUC upon which the 111th loaded their artillery, equipment and men, sank almost immediately. Hank and others in his battery remained afloat until rescued one hour later by an LST. Taken aboard, they were given the only dry uniforms available, U.S. Navy, and the only protective helmet for Hank was one with a corpsmen's red cross (a badge he sadly remembers he could not honor with expertise as he later, on the beach, made his way among the many fallen).

Leaving the LST, the then only replacement to the sunken DUC were makeshift rafts, pontoon type, strung together, upon which they set out to get to the beach, this time with no artillery, not even a rifle or slightest defense. The description of landing on the the beach, Hank has always avoided except to say, "it was utter chaos and everyone was running like hell." He made it to the seawall, picked up a bayonet, punched a hole in this too-big Navy pants and tied them together. Then, along with a couple of buddies, went back to the water's edge to bring back a wounded member of the battery. Someone had morphine and after administering it to the suffering fellow, and marking his forehead with "M," they carried him back to the seawall. There they remained until dark when they made it up the rocky slope which their sacrificial 116th Infantry colleagues has cleared early a.m. Staying there until other ships and supplies landed, they sought out survivors of their 11th artillery, regrouped and went on to St. Lo, all through France, part of Holland and on to the Ruhr River in Germany.

His war experience rendered him eternally grim during his later years as a family man. By the time I was born in 1962, my father was 44 years old. Personally, having fathered my own three children while relatively young, between the ages of 25 and 30, I can't imagine trying to muster up the enthusiasm and love necessary to raise three tiny children, especially withstanding for so many years such compounding agents of sorrow and anxiety. When I was growing up, he was an impatient, cool, detached man. He almost never looked at me when he spoke. Habitually, he clicked his tongue in disgust, and heaved tremendous sighs (something my sisters and I have all inherited, unfortunately). By the time I came along as the last of three children he was pretty miserable. He simply didn't know how to play, but that's hardly surprising. Only after he retired in 1980, when his health began its inexorable decline, did he soften so graciously and tell me that he loved me. Coincidentally, 1980 is the year I started college, so my departure also did something to lighten his step, I'm sure. I am so grateful that he and I laughed quite a bit in his last twenty years, and that he and my children knew each other. He was extremely funny and one of the most generous and heroic people who ever walked the planet, and I was grateful for those glimpses of levity, kindness and courage.

Labels:

events,

history,

miscellaneous blather,

musings,

writing

Location:

New England

Saturday, May 17, 2014

A Few New Designs.

Great illustration makes the job of a designer so much easier. Below are some posters for RISD Illustration talks by the brilliant illustrators John Cuneo and Janet Hamlin, as well as a type treatment for a RISD sponsorship ad for ICON8, the Illustration Conference in Portland Oregon this summer. The latter features a beautiful silkscreen by Branche Coverdale (RISD Illustration '14).

Wednesday, April 30, 2014

Unexpected Cruelty, Typical Kindness.

A couple of days ago I came home to a package on the doorstep. I love packages. Sometimes I buy things online just to have packages shipped to my house, rendering even the dullest day delightful. Nothing like coming home to a brown cardboard box.

This package was unexpected. I could tell it was a book, a small one. It had been shipped from amazon.com, and while I order regularly from their site I wasn't anticipating anything. When I opened it I discovered a hardbound George Saunders book, with no indication of who'd sent it. The cover was pleasant—a white background with embossed script of the title in a sort of rainbow of colors.

At first I was delighted. When I began to read the book, however (a commencement speech which implores us all to be a little kinder by recounting vivid memories of childhood cruelty) anxiety flooded my arms and neck. Even though I was alone in the house, I could feel my face warming with shame. What if someone was trying to teach me a lesson? Had I been unkind? Was this some form of retribution for a slight I'd inflicted? Who would employ cruel irony in such a calculating way? What had I done to deserve this insincere gift, these fluctuating surges of pleasure and shame? Clearly, someone wanted me to think about what I had done, to encourage me to be nice from now on. My transgressions were gaining on me. I felt absolutely miserable.

I stood over the table with my head bowed, thinking about a girl named Gertrude from 6th grade. Her name alone was impetus enough for her classmates to pile on. I don't think I was among her tormenters, but maybe the very human foible of denial was playing tricks on my memory. Even farther back there was the asthmatic kid named Steve, a hulking third grader who stalked me on the playground as inexorably as Frankenstein's monster. I could easily dodge him but my only weapon was my mouth, so we reached what we both sensed was a fair exchange: his physical intimidation vs. my wise-cracking. My mind turned to more current falling outs—ex-lovers and brief flings whose doppelgängers antagonize my conscience in supermarkets and concert halls. Then there are the people I have inevitably offended in my work, with intolerance or disrespect, however unintentional. My mind was awash with dozens of injured faces, all casualties of my callousness. I was so ashamed. I had to stop reading the book. I was beginning to feel sick.

A quick text to my big-hearted friend and former student, Susie Ghahremani, allayed my concerns. I sent her a photo of the book.

"Did you send me this?"

"yep :)"

"Oh thank God. Thought maybe it was someone I had hurt."

"No, I love that you introduced me to George Saunders whom I now love and this seemed topical! It's a graduation speech he made, I believe."

"I had to stop reading until I knew who'd sent it. I began to feel guilty—the way he described his misgivings about not being kinder to "Ellen."

"lol! haven't read it yet! how funny though!"

"Bless you Susie—you have the biggest heart of anyone I know."

She and I share an enjoyment of Saunders' fiction, and this was another in a long line of kind and generous gestures that I should have known was from her. She is one of the most deeply feeling people on the planet and despite our nearly 20 year age difference she mothers me warmly and with good humor. I'm so grateful for her kindness and for what was, in a fleeting moment, forgiveness.

End of story.

Labels:

miscellaneous blather,

musings,

writing

Friday, April 18, 2014

Sunday, April 6, 2014

Wednesday, April 2, 2014

Thursday, March 27, 2014

Wednesday, March 26, 2014

Tuesday, March 18, 2014

Friday, February 7, 2014

Thursday, February 6, 2014

Wednesday, February 5, 2014

Leaving Well Enough Alone.

Left: my chipped tooth, before; Right: a cast of the newly-crafted fang.

A friend and I have been emailing one another about teeth. Not sure how we got on the subject, but she's been trying to convince me that Americans are too obsessed with the perfect grill. Mine are a tangled mess, the result of ancient lines of screwed up mouths from Ireland and The Netherlands. It doesn't seem fair to be a citizen of the most highly developed civilization in history and have such a jumbled mouth.

Some people wear it well. The actor Tom Hardy, for example, has capitalized on a solitary bad tooth, a diamond in the rough which exudes flashes of brilliance when he cracks a smile. A rare glimpse of his snaggletooth is somehow intensely gratifying.

When I was in eighth grade I was playing football in the neighborhood and got kicked in the teeth by another kid's heel when I grabbed his legs to tackle him. While a tiny chip on the back of my front tooth thinned it a little in that spot, making it somewhat transparent and brittle, the shape of my tooth didn't change at all.

Over the years more kicks and misguided chomps took a toll on this poor tooth, and one dentist I knew in my twenties made a night guard for me—a rubber mold of my mouth which was supposed to protect my teeth from further damage due to nocturnal grinding. I quickly learned that dogs love night guards, since mine was licked clean and devoured by a dachshund named Helix less than 24 hours after swimming in my saliva for the first time.

The fatal blow to this tooth was exacted by my daughter Grace in the CompUSA parking lot on Route 2 in Warwick, Rhode Island when she was about six years old. I lifted her to my shoulders after parking the car and in her excitement she clipped me on the chin with both knees. It's taken some time but I have forgiven her.

My mouth clapped shut, the tooth snapped off, and that was that.

Several years later, my dentist—an elderly Rhode Islander with eczema and the mouth of a sailor in a tattoo shop, who worked out of his house and who threw every ounce of his body into assaults on my gaping mouth—suggested that he could fix the tooth with a simple crown. Eager to regain my 8th grade mouth, I consented. I had no idea what I was in for. This was exciting.

While the details are hazy, I do recall that at some point he took a mold with the aid of a woman whom I assumed (for some reason) was his sister-in-law. Calling her away from "The Price Is Right," he asked her to keep the putty in constant motion to prevent drying while he did something else. Gloveless, she grabbed the glob from his hands and played patty-cake with it, all the while chewing gum and ducking in and out of the room to check the Showcase booty. After the mold was finished he cast my upper teeth in plaster and—for some reason—gave it to me as a keepsake, which I have recently put on display in a well-lit glass case in my living room, along with two full sets of my deceased father's dentures, a wind-up Wonder Woman figurine which revolves to the tune of "Jesus Christ, Superstar" and a bunch of odd things I've collected over the years. With the extra putty, the dentist also cast my middle finger, poured plaster into the mold and presented me with "the finger"—a freestanding"fuck you" made infinitely more offensive, considering I was doing it to myself.

Hygiene aside, the most unsettling part of this adventure came after he'd whittled my tooth to little more than a diminutive fang, gave me a sample crown to check if the color matched, and handed me a mirror. Make no mistake: nothing compares to the horror I felt in seeing what was once my front tooth, honed to a bloody stump. I beheld in the mirror the visage of Gollum, smiling meekly, heart dropping to the floor with a thud. My Precious was lost forever.

Few events in life afford glaring self-awareness, and this was one of those critical junctures: a moment when I realized I had been forever altered, having caved to vanity. With any luck, the crown will stay in place until the day I die, but I truly dread the moment that my ruined, wicked, nub-of-a-tooth will be revealed to the world—alarming some dinner companion, its porcelain costume falling onto my plate, leaving me to once again lament that I should have left well enough alone.

Tuesday, February 4, 2014

Lost and Found.

Who can explain why it's sometimes so difficult to get started, and at other times we can't stop ourselves from creating things? This is such a mystery to me. I'm sure someone has an answer.

In between illustration jobs I try to paint. It keeps me fresh and a bit more daring, allowing me to practice freely and follow intuition with no obligation. I get so sick of painting unbridled joy.

I found a stack of paintings I started several years ago. They were a little damaged from being laid on top of one another, and they weren't resolved at all. Most were pretty bad, even though they started good. This excited me.

I have put them in a pile on my table. I woke at 4:00am today, Paavo between my knees. I allowed him to sleep with me last night, a reward for us both. I didn't bother getting dressed, other than pulling on a sweatshirt and knit cap, and I walked in the dark to my studio, the snow lighting my way.

In between illustration jobs I try to paint. It keeps me fresh and a bit more daring, allowing me to practice freely and follow intuition with no obligation. I get so sick of painting unbridled joy.

I found a stack of paintings I started several years ago. They were a little damaged from being laid on top of one another, and they weren't resolved at all. Most were pretty bad, even though they started good. This excited me.

I have put them in a pile on my table. I woke at 4:00am today, Paavo between my knees. I allowed him to sleep with me last night, a reward for us both. I didn't bother getting dressed, other than pulling on a sweatshirt and knit cap, and I walked in the dark to my studio, the snow lighting my way.

Sunday, February 2, 2014

Wednesday, January 15, 2014

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)