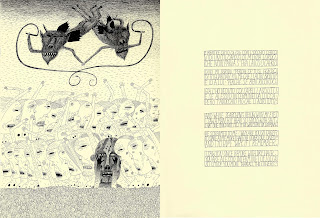

Inferno XXVII: The Taking of Guido da Montefeltro

Ink on paper, 2021

22 x 15”

Inferno XXVII continues the theme of souls entrapped in flames, when Dante and Virgil meet Guido da Montefeltro, a Ghibelline captain of the 13th century whose opposition to the Church (the Guelphs) was reconciled many years later when he became a Franciscan monk. Having steered clear of military conflict for several years, Guido was eventually cajoled by Pope Boniface VIII to rejoin the fray, this time against the Ghibelline army he once led. Ultimately, at his death, the faithful Franciscan was poised to be spirited away to heaven by St. Francis, but the angel of darkness appeared to intervene at the last moment, sealing his fate in hell, which we read about in Inferno XXVII. In this drawing, Guido is seen in deathly repose at the bottom, with Francis at the top of image. Sandwiched in between—in Escher-like, figure-ground interplay—is the angel of darkness, with Boniface's tiara crowning his hideous face. The latter touch was an instinctual move to bring the evil Pope into the picture.

I have seven more drawings to complete in this series. The project began almost five years ago, and I'm ashamed that it's taking so long to finish. No excuses, but the deeper my descent into hell, the more involved the drawings become, and I sense that I will really need to improve with each to ensure that I wrap it up with a fitting crescendo of density and pathos. In this sense my process, although plodding and often really enjoyable, is a metaphor for Dante's journey. I do need to pick up the pace and now that I have left behind many years of administrative work I hope to dedicate all of my time this summer to finishing the remaining drawings. Each drawing can take days to complete, depending on the task I've created for myself, and I simply haven't had a lot of that unfettered time to get them done. An hour here or there truly breaks the momentum, so I need to find better ways to resume and set aside the work in fits and starts while still making progress.