In doing some genealogical research last winter I uncovered (online, of all places, and quite randomly) the passport applications of my grandparents, my uncle and my father—eerie snapshots of a young family about to embark on a new life in Europe, not knowing that the man of the house would be dead within months. My father was 3 years old. He's the small child in the center of the third photograph.

Dad learned to swim when he was thrown off a bridge by his bully of a brother (five years his senior, aided by a bunch of neighborhood toughs). With his father dead and his brother a juvenile delinquent who spent most of his time carousing with other punks from the neighborhood, my dad was left to wait on a house full of spinsters and widows. His mother returned from Germany to Atlantic City to be with her sisters and mother for many protracted years of mourning (I have seen photos of her in black dress and veil in bright sunlight on the Boardwalk—a frail, inky specter of grief who couldn't let go of loss). My father lived in the big, old, tudor house at 4710 Theresa Place with his grandmother, mother and four maiden aunts, all psychically exhausting women who knew nothing of responsibility, having been pampered all their lives by their father, a wealthy railroad man who had long since left behind life on earth and a comfortable salary. But there were stories of fun (or, at least, funny) times too. My dad bragged about having broken too many bones to count with stunts like jumping from balconies with his neighbor and boyhood pal Billy Fox. He loved hanging out on the beach all day to idolize the legendary Atlantic City lifeguards, and he told me stories about beating sand sharks to death on the shore, just for the hell of it, of sun poisoning, and of cutting open his palm while trying to skim slate over the ocean waves. One of the brightest moments of his life occurred in October 1927, when Charles Lindbergh landed his plane at Bader Field in Atlantic City, following his earth-shifting, heroic transatlantic flight. My father had laid in the grass all day, his nine-year-old eyes scanning every inch of the sky for the wings of the Spirit of St. Louis, inscribed with large block letters: NX-211. He saw the plane fly right overhead and rushed to the airport. What a thrill that must have been.

My dad had a long and challenging life. He grew up in decadent, mob-infested Atlantic City in the 1920's and 30s. He told the story from time-to-time of watching from his window as Dutch Shultz' men shot from the bushes of the house next door at windows on the second floor. When I was about ten, I found a photo of him at the same age. If not for the uber-masculine, defiant expression on his face, I was looking in a mirror. There he was on an Atlantic City sidewalk, dressed in a shirt and tie and sitting on a pony: chin thrust forward, scowling brow, piercing blue eyes. I remember having the uneasy feeling that he would have been my nemesis if we had been boyhood neighbors. He scared me.

Dad learned to swim when he was thrown off a bridge by his bully of a brother (five years his senior, aided by a bunch of neighborhood toughs). With his father dead and his brother a juvenile delinquent who spent most of his time carousing with other punks from the neighborhood, my dad was left to wait on a house full of spinsters and widows. His mother returned from Germany to Atlantic City to be with her sisters and mother for many protracted years of mourning (I have seen photos of her in black dress and veil in bright sunlight on the Boardwalk—a frail, inky specter of grief who couldn't let go of loss). My father lived in the big, old, tudor house at 4710 Theresa Place with his grandmother, mother and four maiden aunts, all psychically exhausting women who knew nothing of responsibility, having been pampered all their lives by their father, a wealthy railroad man who had long since left behind life on earth and a comfortable salary. But there were stories of fun (or, at least, funny) times too. My dad bragged about having broken too many bones to count with stunts like jumping from balconies with his neighbor and boyhood pal Billy Fox. He loved hanging out on the beach all day to idolize the legendary Atlantic City lifeguards, and he told me stories about beating sand sharks to death on the shore, just for the hell of it, of sun poisoning, and of cutting open his palm while trying to skim slate over the ocean waves. One of the brightest moments of his life occurred in October 1927, when Charles Lindbergh landed his plane at Bader Field in Atlantic City, following his earth-shifting, heroic transatlantic flight. My father had laid in the grass all day, his nine-year-old eyes scanning every inch of the sky for the wings of the Spirit of St. Louis, inscribed with large block letters: NX-211. He saw the plane fly right overhead and rushed to the airport. What a thrill that must have been.

Having left for the University of Virginia, where he was president of his fraternity and captain of the swim team (but unhappy in both roles because, as he said, his main responsibility was to keep drunk college boys out of trouble), my father enlisted post-college on 13 December 1941 and was shipped off to Europe to join the allied forces. Twenty-three years old, he indicated on his enlistment form (which I also, miraculously, found online) that his occupation was "actor." This puzzled and amused me; my mom explained that he and Billy Fox, unsure of what their lots in life would be, had planned to leave for Hollywood and make it in show business. "We're both good-looking fellas" Billy had said.

My dad was (tragically) on board the Queen Mary on 27 September 1942, when it cut through the much smaller British cruiser, HMS Curaçao, killing 329 of the 430 men on board. On his way to join the allied forces of the War, he was sleeping in his bunk after a night of duty (in what was once the cocktail lounge of the luxury liner during its non-military years) when the Queen Mary rammed the Curaçao. I have some articles about that too—one with a photocopy of the Queen Mary marked up with his meticulous handwriting, noting the position of his quarters on the ship.

My mom became a voice for whatever war narratives he would allow to unravel. The most harrowing of these experiences may have been his involvement in the battle of Normandy on Omaha Beach on D-Day, exactly 70 years ago today. Undoubtedly, he experienced both grief and intense fear, and while news media contacted him many times over the years to tell his story, he always declined. I've learned over the years that many of those men were reluctant to discuss the experience. It must have been horrible. I feel fortunate that he did relate the facts to my mom, who is now 94. She shared this brief account of his experience in 1998:

Hank Brinkerhoff was with the famed 29th Division. The 111th Field Artillery (his outfit) followed the 116th Infantry Regiment, the first to arrive on Omaha Beach on D-Day. The 11th were to be the infantry simultaneous back-up but the DUC upon which the 111th loaded their artillery, equipment and men, sank almost immediately. Hank and others in his battery remained afloat until rescued one hour later by an LST. Taken aboard, they were given the only dry uniforms available, U.S. Navy, and the only protective helmet for Hank was one with a corpsmen's red cross (a badge he sadly remembers he could not honor with expertise as he later, on the beach, made his way among the many fallen).

Leaving the LST, the then only replacement to the sunken DUC were makeshift rafts, pontoon type, strung together, upon which they set out to get to the beach, this time with no artillery, not even a rifle or slightest defense. The description of landing on the the beach, Hank has always avoided except to say, "it was utter chaos and everyone was running like hell." He made it to the seawall, picked up a bayonet, punched a hole in this too-big Navy pants and tied them together. Then, along with a couple of buddies, went back to the water's edge to bring back a wounded member of the battery. Someone had morphine and after administering it to the suffering fellow, and marking his forehead with "M," they carried him back to the seawall. There they remained until dark when they made it up the rocky slope which their sacrificial 116th Infantry colleagues has cleared early a.m. Staying there until other ships and supplies landed, they sought out survivors of their 11th artillery, regrouped and went on to St. Lo, all through France, part of Holland and on to the Ruhr River in Germany.

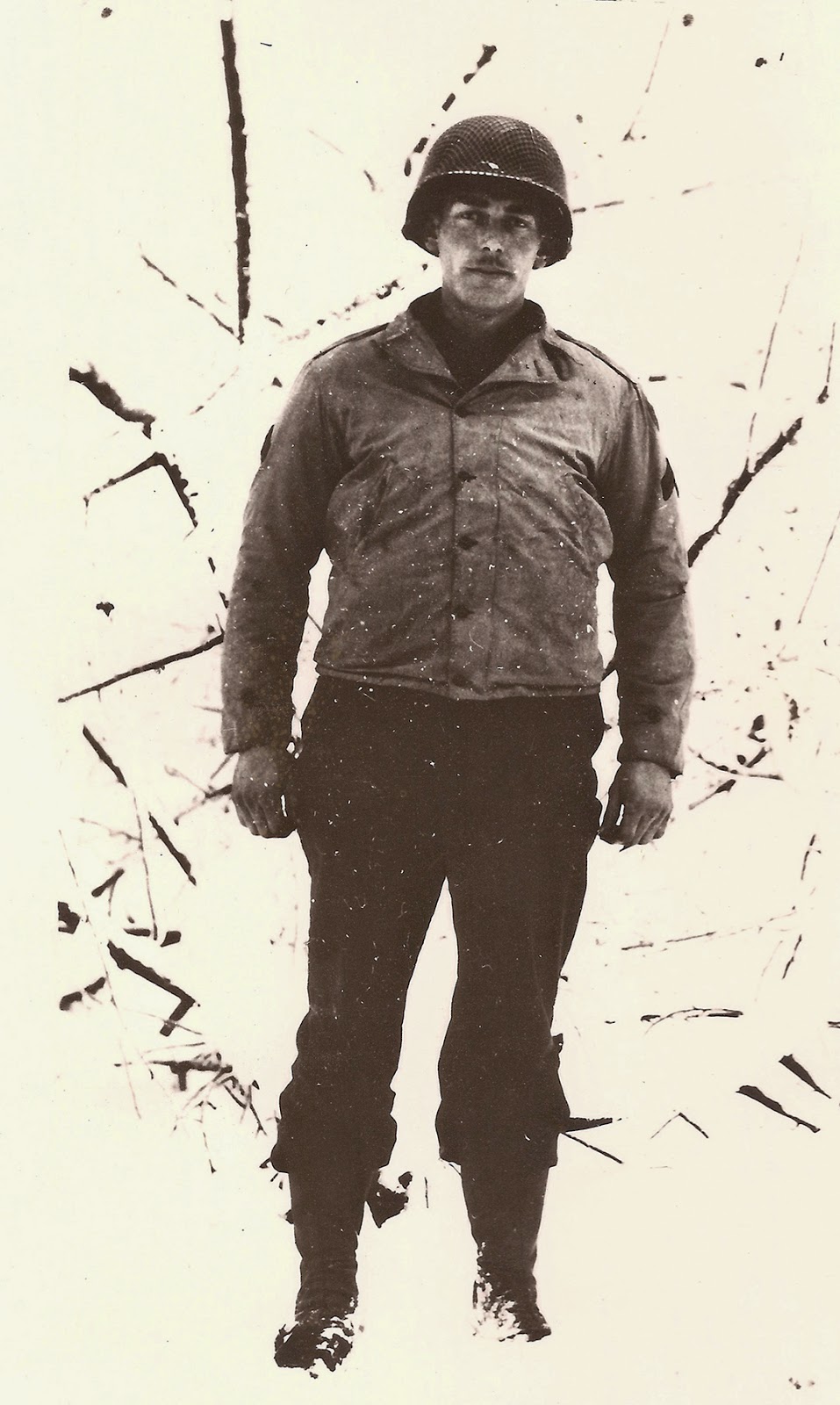

His war experience rendered him eternally grim during his later years as a family man. By the time I was born in 1962, my father was 44 years old. Personally, having fathered my own three children while relatively young, between the ages of 25 and 30, I can't imagine trying to muster up the enthusiasm and love necessary to raise three tiny children, especially withstanding for so many years such compounding agents of sorrow and anxiety. When I was growing up, he was an impatient, cool, detached man. He almost never looked at me when he spoke. Habitually, he clicked his tongue in disgust, and heaved tremendous sighs (something my sisters and I have all inherited, unfortunately). By the time I came along as the last of three children he was pretty miserable. He simply didn't know how to play, but that's hardly surprising. Only after he retired in 1980, when his health began its inexorable decline, did he soften so graciously and tell me that he loved me. Coincidentally, 1980 is the year I started college, so my departure also did something to lighten his step, I'm sure. I am so grateful that he and I laughed quite a bit in his last twenty years, and that he and my children knew each other. He was extremely funny and one of the most generous and heroic people who ever walked the planet, and I was grateful for those glimpses of levity, kindness and courage.

1 comment:

Robert, this, from 6 June 2014, was what I'd originally read. So you apparently didn't grow up in AC. We lived briefly on Bartram Ave in 1950, not far from Teresa Place. I remember falling into a rose bush near the beach and Doctor Sweeney stitching me up (still have faint scar), giving me my first chocolate covered cherries. Downbeach, near Ventnor was bleak, at least compared to the rest of the town.

Post a Comment